Recently, I was playing around with the question – what is the best attribute to have at the gemba? At first, I thought that perhaps it could be creativity. I soon realized that this is like Superman, a superhero with all of the answers. This does not align with the idea of the people system or the thinking production system – generating ideas bottom-up. Then I thought, perhaps the best attribute to have at the gemba is the ability to listen. I felt that I was on the right track with this thought. I soon came to the realization that the best attribute to have at the gemba is “Anekantvada”. Anekantvada is a Sanskrit word that translates as “many + ends + -ness” or “many sidedness”. This idea comes from one of the ancient religions from India called Jainism. Jainism is also famous for its other contribution – Ahimsa or non-violence. We can view anekantvada as cognitive ahimsa – in other words, not being violent or hostile to others’ ideas. The main idea of anekantvada is that Reality lies outside of your mind. What you have inside your mind is your perspective or your own version of a narrative regarding the reality outside. Thus, your perspective is a poorly translated and limited copy of the reality outside and your understanding of the reality is incomplete. Anekantvada requires you to look at multiple perspectives from other people to truly understand reality, as one perspective alone is incomplete. All knowledge is contextual. We cannot separate the object and the viewer, when we are creating knowledge about something. This means that if there is more than one viewer, the knowledge created will be different.

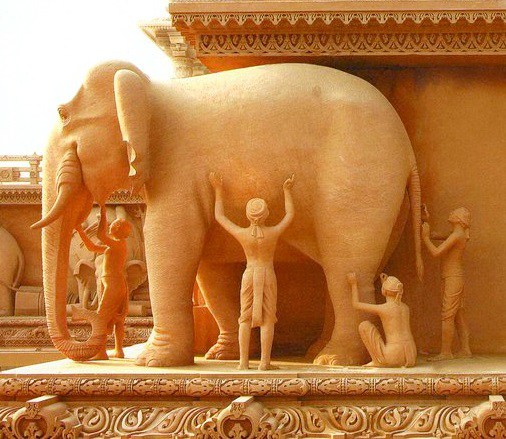

The story of the blind men and the elephant is a very common story that explains the different perspectives of reality. The story originated with Jainism to explain anekantvada. In the Jain version of the story, there were six blind men who came to “see” the elephant, and each person felt one part of the elephant and described the elephant from his perspective. Each perspective was different because each person felt a different part of the elephant. One person felt the ear and said that the elephant was like a fan, while another felt the tail and said that the elephant was like a rope. The king happened to be there at that time, and listened to the blind men fighting on who was correct. The king told them that while each of them was partially correct, when taken one perspective at a time the truth was incomplete.

From the Jain philosophy, reality and thus the truth itself is complex and always has multiple aspects. Even if you can experience reality, you cannot express the reality completely. The best we can do is like one of the blind men – give our version, a partial expression of truth. In Jain philosophy, this idea can be explained by “Syadvada”. The root word “Syad” can be translated as “perhaps”. Using this approach, we can express anekantavada by adding “perhaps” in front of our expression of reality. An example would be to say – “perhaps the dress is blue and black”.

The two quotations below add more depth to what we have discussed so far:

“To deny the coexistence of the mutually conflicting viewpoints about a thing would mean to deny the true nature of reality.” – Acharang Sutra

“The water from Ocean contained in a pot can neither be called an ocean or a non-ocean, but simply a part of the ocean. Similarly, a doctrine, though arising from absolute truth can neither be called a whole truth or a non-truth.” – Tattvarthaslokavartikka.

The idea of anekantvada requires you to respect others’ ideas. It also makes you realize that your version of reality is incomplete. Thus, when you are at the gemba telling others what to do, you are not open to others’ viewpoints. You are going with your version of the story – it should be easy to do this, the way I tell you. Anekantvada brings a new layer of meaning to Respect for People, one of the two pillars of the Toyota Way. Take the example of Standard Work – Do you create it in vacuum and ask the operators to follow it? When there is a problem on the floor, do you figure out what happened and then require the operators to follow your one “true” way?

All knowledge, judgment and decisions we make depends upon the context of the reality, and it may make sense only when viewed in that context. Why did the operator omit step 2 of the work instructions that led to all of these rejects? This reminds me of the principle of Local Rationality, an idea that I got from Sidney Dekker [1]. Local Rationality refers to the idea that people do what make the most sense to them, at any given time. This decision may have led to some disaster, but the operator(s) did what made sense to them at that time. When you look at things this way, you start to view it from the operator’s standpoint, and finally may be able to understand what happened from a different perspective.

I will finish with a story about context:

Two students came to study under the master. They were both fond of smoking. The first day itself, the first student went to the teacher and asked whether he could smoke when he was meditating. The teacher told him that he could not do that.

Feeling sad, the first student went outside to meditate under the tree. There he saw the second student under a tree smoking. The first student asked him, “Why are you smoking? Don’t you know that our teacher does not like it when you smoke and meditate?”

The second student responded that he had asked the teacher and the teacher said that he could smoke.

The first student was confused and asked the second student, what exactly did he ask the teacher.

The second student said, “I asked him if I can meditate when I smoke.”

The first student replied, “That makes sense. I asked him if I can smoke when I meditated.”

Always keep on learning…

In case you missed it, my last post was The Socratic Method: