In today’s post, I am looking at the phrase “Organizational Closure” and the concept of autopoiesis. But before that, I would like to start with another phrase “Information Tight”. Both of these phrases are of great importance in the field of Cybernetics. I first came across the phrase “Information Tight” in Ross Ashby’s book, “An Introduction to Cybernetics”. Ross Ashby was one of the pioneers of Cybernetics. Ashby said: [1]

Cybernetics might, in fact, be defined as the study of systems that are open to energy but closed to information and control— systems that are “information‐tight”.

This statement can be confusing at first, when you look at it from the perspective of Thermodynamics. Ashby is defining “information tight” as being closed to information and control. The Cybernetician, Bernard Scott views this as: [2]

…an organism does not receive “information” as something transmitted to it, rather, as a circularly organized system it interprets perturbations as being informative.

Here the “tightness” refers to the circular causality of the internal structure of a system. This concept was later developed as “Organization Closure” by the Chilean biologists, Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela. [3] They were trying to answer two questions:

- What is the organization of the living?

- What takes place in the phenomenon of perception?

In answering these two questions, they came up with the concept of Autopoiesis. Auto – referring to self, and poiesis – referring to creation or generation. Autopoiesis means self-generation. Escher’s “Drawing Hands” is a good visualization of this concept. We exist in the continuous production of ourselves.

As British organizational theorist, John Mingers put it: [4]

Maturana and Varela developed the concept of autopoiesis in order to explain the essential characteristics of living as opposed to nonliving systems. In brief, a living system such as a cell has an autopoietic organization, that is, it is ”self-producing. ” It consists of processes of production which generate its components. These components themselves participate in the processes of production in a continual recursive re-creation of self. Autopoietic systems produce themselves and only themselves.

John H Little provides further explanation: [5]

Autopoietic systems, are self-organizing in that they produce and change their own structures but they also produce their own components… The system’s production of components is entirely internal and does not depend on an input-output relation with the system environment.

Two important principles underlying autopoiesis are “structural determinism” and “organizational closure.” To understand these principles, it is first necessary to understand the difference between “structure” and “organization” as Maturana uses these terms. “Organization” refers to the relations between components which give a system its identity. If the organization of a system changes, its identity changes. “Structure” refers to the actual components and relations between components that make up a particular example of a type of system.

Conceptually, we may understand the distinction between organization and structure by considering a simple mechanical device, such as a pencil. We generally have little difficulty recognizing a machine which is organized as a “pencil” despite the fact that pencil may be structurally built in a variety of ways and of a variety of materials. One organizational type, therefore may be manifested by any number of different structural arrangements.

Marjatta Maula provides additional information on the “organization” and “structure”, two important concepts in autopoiesis.

In autopoiesis theory, the concepts ‘organization’ and ‘structure’ of a system have a specific meaning. ‘Organization’ refers to an idea (such as an idea of airplane or a company in general). ‘Structure’ refers to the actual embodiment of the idea (such as a specific airplane or a specific company). Thus, ‘organization’ is abstract but ‘structure’ is concrete (Mingers, 1997). Over time an autopoietic system may change its components and structure but maintain its ‘organization.’ In this case, the system sustains its identity. If a system’s ‘organization’ changes, it loses its current identity (von Krogh & Roos, 1995). [6]

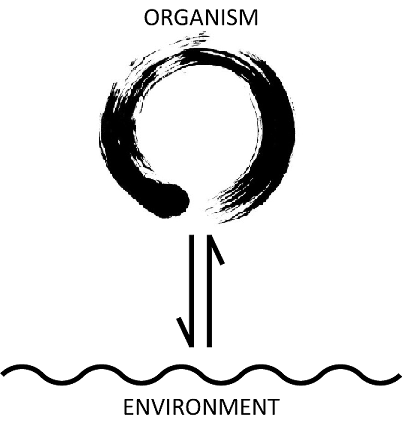

The most important idea that Maturana and Varela put forward was that an autopoietic system does not take in information from its environment and an external agent cannot control an autopoietic system. Autopoietic systems are organizationally (or operationally) closed. That is to say, the behavior of the system is not specified or controlled by its environment but entirely by its own structure, which specifies how the system will behave under all circumstances. It is as a consequence of this closure that living systems cannot have “inputs” or “outputs”-nor can they receive or produce information-in any sense in which these would have independent, objective reality outside the system. Put in another way, since the system determines its own behavior, there can be no “instructive interactions” by means of which something outside the system determines its behavior. A system’s responses are always determined by its structure, although they may be triggered by an environmental event.[7]

Although organizationally closed, a system is not disconnected from its environment, but in fact in constant interaction with it. Maturana and Varela (1987) call this ongoing process “structural coupling” (p. 75). System and environment (which will include other systems) act as mutual sources of perturbation for one another, triggering changes of state in one another. Over time, provided there are no destructive interactions between the system and the medium in which it realizes itself (i.e., its environment), the system will appear to an observer to adapt to its environment. What is in fact happening, though, is a process of structural “drift” occurring as the system responds to successive perturbations in the environment according to its structure at each moment. [7]

In other words, the idea of an organism as an information processing agent is a misunderstanding. When you look at it further, although it might appear as strange, little by little, it might make sense. Think about a classroom, a teacher is giving a lecture and the same “information” reaches the students. However, what type and amount of “information” is taken in depends on each individual student. Maturana explains it as the teacher makes the selection (in the form of the lecture), however, the teacher cannot make the student accept the “information” in its entirety. A loose analogy is a person pushing a button on a vending machine. The internal structure of the machine determines how to react. If the machine does not have a closed structure inside, it cannot react. The pressing of the button is viewed as a perturbation, and the vending machine reacts based on its internal structure at that point in time. If the vending machine was out of order or if there was something blocking the item, the machine will not dispense even if the external agent “desired” the machine to reach in a specific way.

According to Maturana, all systems consisting of components are structure-determined, which is to say that the actual changes within the system depend on the structure itself at that particular instant. Any change in such a system must be a structural change. If this is the case, then an environmental action cannot determine its own effect on a system. Changes, or perturbations in the environment can only trigger structural change or compensation. “It is the structure that determines both what the compensation will be and even what in the environment can or cannot act as a trigger” (Mingers, 1995, p. 30).

It is the internal structure of the system at any point in time that determines:

- all possible structural changes within the system that maintain the current organization, as well as those that do not, and

- all possible states of the environment that could trigger changes of state and whether such changes would maintain or destroy the current organization (Mingers, 1995, p. 30).[5]

As we understand the idea of autopoiesis, we start to realize that it has serious implications. Our abstract concept of a process is shown below:[5]

INPUT -> PROCESS -> OUTPUT

In light of autopoiesis, we can see that this abstraction does not make sense. An autopoietic system cannot accept inputs. We treat information and knowledge as a commodity that can be easily coded, stored and transferred. Again, in the light of autopoietic systems, we require a new paradigm. As Little continues:[5]

An organizationally closed system is one in which all possible states of activity always lead to or generate further activity within itself… Organizationally closed systems do not have external inputs that change their organization, nor do they outputs in terms of their organization. Autopoietic systems are organizationally closed and do not have inputs and outputs in terms of their organization. They may appear to have them, but that description only pertains to an observer who can see both the system and its environment, and is a mischaracterization of the system. The idea of organizational closure, however, does not imply that such systems have no interactions with their environment. Although their organization is closed, they still interact with their environment through their structure, which is open.

John Mingers provides further insight: [4]

Consider the idea that the environment does not determine, but only triggers neuronal activity. Another way of saying this is that the structure of the nervous system at a particular time determines both what can trigger it and what the outcome will be. At most, the environment can select between alternatives that the structure allows. This is really an obvious situation of which we tend to lose sight. By analogy, consider the humming computer on my desk. Many interactions, e.g., tapping the monitor and drawing on the unit, have no effect. Even pressing keys depends on the program recognizing them, and pressing the same key will have quite different effects depending on the computer’s current state. We say, “I’ll just save this file,” and do so with the appropriate keys as though these actions in themselves bring it about. In reality the success (or lack of it) depends entirely on our hard-earned structural coupling with the machine and its software in a wider domain, as learning a new system reminds us only too well.

Another counterintuitive idea was put forth by the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann, that further elaborates the autopoietic system’s autonomous nature and the “independence” from the external agent:

The memory function never relates to facts of the outer world . . . but only to the states of the system itself. In other words, a system can only remember itself.

An obvious question at this point is – If a system is so independent of its environment, how does it come to be so well adjusted, and how do systems come to develop such similar structures?[4]

The answer lies in Maturana’s concept of structural coupling. An autopoietic organization is realized in a particular structure. In general, this structure will be plastic, i.e., changeable, but the changes that it undergoes all maintain auto poiesis so long as the entity persists. (If it suffers an interaction which does not maintain autopoiesis, then it dies.) While such a system exists in an environment which supplies it with necessities for survival, then it will have a structure suitable for that environment or autopoiesis will not continue. The system will be structurally coupled to its medium. This, however, is always a contingent matter and the particular structure that develops is determined by the system. More generally, such a system may become structurally coupled with other systems-the behavior of one becomes a trigger for the other, and vice versa.

Maturana and Varela did not extend the concept of autopoiesis to a larger level such as a society or an organization. Several others took this idea and went further. [8]

Using the tenets of autopoietic theory (Zeleny: 2005), he interprets organizations as networks of interactions, reactions and processes identified by their organization (network of rules of coordination) and differentiated by their structure (specific spatio-temporal manifestations of applying the rules of coordination under specific conditions or contexts). Following these definitions, Zeleny argues that the only way to make organizational change effective is to change the rules of behavior (the organization) first and then change processes, routines, and procedures (the structure). He explains that it is the system of the rules of coordination, rather than the processes themselves, that defines the nature of recurrent execution of coordinated action (recurrence being the necessary condition for learning to occur). He states: ‘Organization drives the structure, structure follows organization, and the observer imputes function’.

Espejo, Schumann, Schwaninger, and Bilello (1996)adopt similar terminology, but instead of organization they refer to an organization’s identity as the element that defines any organization, explaining that it is the relationships between the participants that create the distinct identity for the network or the group. Organization is then defined as ‘a closed network of relationships with an identity of its own’. While organizations may share the same kind of identity, they are distinguished by their structures. People’s relationships form routines, involving roles, procedures, and uses of resources that constitute stable forms of interaction. These allow the integrated use and operation of the organization’s resources. The emergent routines and mechanisms of interaction then constitute the organization’s structure. Hence, just like any autopoietic entity, organizations as social phenomena are characterized by both an organization (or identity) and a structure. The rules of interaction established by the organization and the execution of the rules exhibited by the structure form a recursive bond.

Final Words:

I highly encourage the readers to pursue understanding of autopoiesis. It is an important concept that requires a shift in your thinking.

I will finish off with an example of autopoietic system that is not living. I am talking about von Neumann probes. Von Neumann probes are named after John von Neumann, one of the most prolific polymaths of last century. A von Neumann probe is an ingenious solution for fast space exploration. A von Neumann probe is a spacecraft that is loaded with an algorithm for self-replication. When it reaches a suitable celestial body, it will mine the required raw materials and build a copy of itself, complete with the algorithm for self-replication. The new spacecraft will then proceed to explore the space in a different direction. The self-replication process continues with every copy in an exponential manner. You may like this post about John von Neumann.

Always keep on learning…

In case you missed it, my last post was The Illegitimate Sensei:

[1] An Introduction to Cybernetics – Ross Ashby

[2] Second-order cybernetics: an historical introduction – Bernard Scott

[3] Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living – Francisco Varela and Humberto Maturana

[4] The Cognitive Theories of Maturana and Varela – John Mingers

[5] Maturana, Luhmann, and Self-Referential Government – John H Little

[6] Organizations as Learning Systems – Marjatta Maula

[7] Implications of The Theory Of Autopoiesis For The Discipline And Practice Of Information Systems – Ian Beeson

Reblogged this on Systems Community of Inquiry.

LikeLike

This piece is a good overview. The concepts use to describe or explain ‘life’ are still much too ambiguous, but this fact is still not recognized. They are still much too anthropomorphic, and thus strictly arbitrary. Even the concept of ‘living’ system (extremely anthropomorphic concept), has never been fully agreed upon, and is not at all formally defined. It is just some list of ambiguous, anthropomorphic properties, which is absolutely unusable for any understanding of the underlying mechanism of ‘autopoesis’.

Even this concept is unusable, because it suggests that an organism or ‘identity’ acts according to some purpose of its own, like ‘minimization of free energy’, or ‘self-organization’. Every considered boundary is arbitrary, and does not provide any useful insight for understanding the underlying principle. Also, the current manifestations of this underlying principle are an arbitrary selection of possible manifestations, and their relative elaborate complexity obfuscate the simplicity of this underlying, generic principle, and point us in the wrong directions.

It cannot be understood from the perspective of the ‘living unit’, but only from the perspective of the hosting system. A system will always dissipate local energetic differences in the cheapest way (relative to its current state). In some weather-systems, this yields what we call a ‘tornado’. The tornado itself is not ‘autopoetic’; it is the hosting weather-system that can dissipate its energetic local differences easiest by use of this ‘organization’. At some point, this dynamic will saturate/exhaust, and disappear. What we call ‘life’ is a nonlinear extrapolation into an intricate hierarchy of such saturation processes. Our current ecocystem is just a local (in time and space) maximum of entropy production. Living organisms can be described as chaotic attractors of fractal infrastructures for entropy production, local maximae of dissipative infrastructures. Abstract, technical stuff.

Wrote several publications on this, for anyone who is really interested.

LikeLike

Thank you for your thoughtful comment.

LikeLike

Would you say structural coupling implies adaptivity ……If no,pls explain

LikeLike

My understanding is that structural coupling represents a history. The most important distinction to make is that environment does not cause any adaptiveness.

The structure of the organism and the perturbations from the environment results in a set of interactions. “We speak of structural coupling whenever there is a history of recurrent interactions leading to the structural congruence between two (or more) systems.”

While this can be seen as adaptations, I don’t know if that was what Maturana intended.

LikeLike

Harish, have you heard about the work of theoretical biologist, Robert Rosen? Particularly his books, ‘Life Itself’ and ‘Essays on Life Itself’… I think that his idea regarding the distinction between a living organism and a mechanism is highly relevant to these ideas. As well as the seminal paper by Varela titled ‘A Calculus of Self-Reference’ based on the book, ‘Laws of Form’ by G Spencer Brown. Thank you for this information. I think it is well presented and very helpful. You might also find this paper by Marks-Tarlow et al to be helpful in understanding the significance of these concepts:http://www.markstarlow.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Varela-and-the-Uroboros.pdf

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your thoughtful comment and the reference. I am a fan of GSB and LoF. I have read Varela’s paper.

Thanks again. I will definitely check Rosen’a works.

-Harish

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that Rosen’s work has been sadly overlooked and, for the most part, ignored. And yet he makes a critical distinction: while mechanisms are entirely deterministic and can be described by predicative mathematics, living organisms are fundamentally more generic and require description using impredicative mathematics. This is actually huge. There is a very nice summary of ‘Essays on Life Itself’ provided by Jan Höglund who reviewed the book for GoodReads.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3168855-essays-on-life-itself

I agree with Jan’s conclusion to this review:

Conclusions

If Robert Rosen is right — and I think he is — then it does change the way we look at our world. The mathematical machinery is limited in what it allows us to capture about the world and necessarily misses most of what is really going on. Rosen doesn’t say that we can learn nothing from computable models. His point is that inherently computable dynamical systems miss most of reality.

Computability imposes very strong limitations on entailment. It is precisely these limitations that allows them to be expressed as ‘software.’ However, meaningful distinctions cannot be made between ‘software’ and ‘hardware’ in organisms. Almost everything about organisms is entailed from something else. Rosen asserts, furthermore, that organisms and human systems are very much alike.

The ramifications of Robert Rosen’s ideas are very deep indeed. It’s a brilliant book!

I would second that impression….

LikeLike

And when you put together Rosen’s work with Varela and GSB, there is a very powerful ‘narrative’ that relates to the symbol of the ‘Ouroboros’ which is a fundamental symbol in the Creation myths of multiple cultures as pointed out by Erich Neumann in the first chapter of his book, ‘The Origins and History of Consciousness’. This whole train of investigation on my part was triggered through coming across reference to the Ouroboros in a cryptic passage from the Zohar which I have been studying.

What is most important is that it relates to a completely new (although also ‘old’ as in indigenous culture and certain mystical faith traditions) narrative, or ‘alternative’ narrative to the dominant current narrative of the Western world which tells us that we are separated from each other and the world, that we compete for scarce resources, and that we should embrace an ethos of ‘what’s mine is mine and what’s yours is yours’ without consideration to giving, or responsibility for the welfare of an Other. This narrative inevitably leads to violence and injury.

This was the general ethos maintained in Sodom and Gomorrah and we know what happened to those cities…..

LikeLike